Last Updated on May 14, 2024 by Ecologica Life

Microplastics have pervaded every corner of our planet, from the vast expanses of our oceans to the very air we breathe. These tiny particles have been found not only in the marine environment, but also in more unexpected places, including cow’s milk and even human blood samples, revealing the widespread and concerning reach of microplastic contamination.

We still know too little about how microplastics affect us and life in general. In this article, we will explore what recent scientific evidence tells us about how ingestion of microplastics is affecting aquatic mammals. We will also touch upon what solutions to the plastic crisis.

What are microplastics? Should you be worried?

Table of Contents

Plastics in the Ocean

Plastic waste is a modern problem that is both societal and ecological in nature. We find it everywhere in our daily lives. Unfortunately, plastic has been found in the stomachs of whales, turtles, fish and other marine life.

Plastic currently makes up around 60-80% of the waste found in the ocean and is considered the biggest threat to marine life, even more than other threats such as pollution, climate change, resource over-exploitation, and invasive species.1

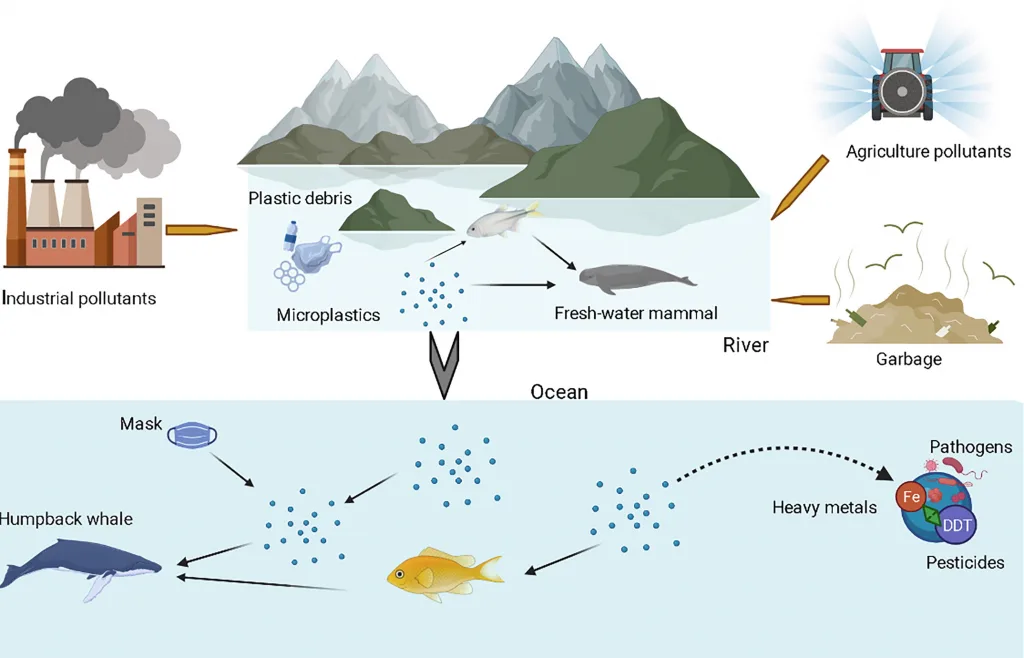

Plastic debris is carried long distances by winds, rivers, and ocean currents. Every year, between 5 and 13 million tons of plastic waste end up in the ocean, spreading from coastal areas to the seabed, through open ocean currents and even to distant polar regions.1

What are Microplastics?

Definitions and Origins

Plastics break down into small particles less than 5mm in size, known as microplastics (MPs). MPs can be either primary or secondary. Primary MPs intentionally produced and can be found in some cosmetic scrubs. Secondary MPs come from larger plastics that have broken down into smaller ones.

Sources and Impact

Sources of microplastics include the likely suspects such as plastic bags, but also unexpected sources such as synthetic clothing (e.g. polyester), as well as infant baby bottles and tea bags. In theory, anything that has or is plastic can produce microplastics. This is especially true in the presence of heat and UV rays.

It’s even been reported that due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 1370 trillion MPs would have entered coastal marine environments by 2020 due to surgical masks discarded around the world.2

Due to their physical and chemical nature, plastic and microplastic debris persist in the environment for long periods of time.

Why Microplastics Are Dangerous for Aquatic Mammals

Ingestion

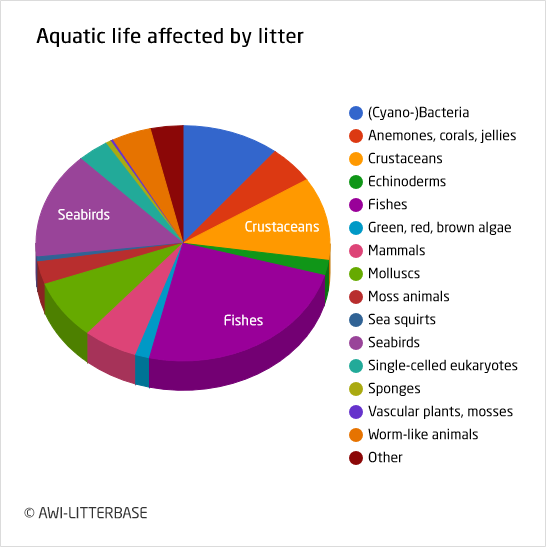

Research suggests that whales ingest 10 million microplastic particles every day. To date, some 4076 species have been reported to be affected by marine debris ( LITTERBASE, accessed 17 February 2024). Of these, plastic ingestion has been reported among 655 species of aquatic mammals.

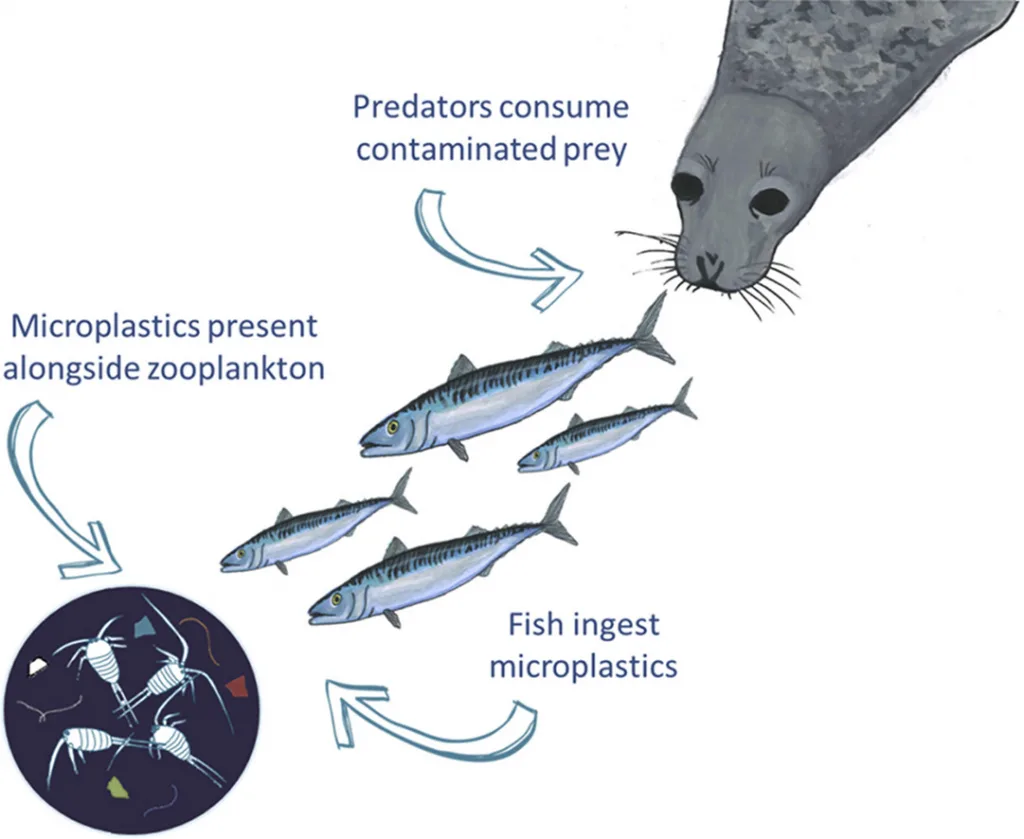

Microplastics have even been found in the scat (faeces) of grey seals living in a sanctuary.3 This is where you might expect plastic pollution to be low, but there is evidence that MPs can move up the food chain.3 These seals obtained MPs by ingesting fish that had ingested MPs when consuming zooplankton.

Toxicity Concerns

MP toxicity hasn’t been thoroughly investigated in aquatic mammals. It appears that comparatively more research has been done on MP toxicity in land mammals. What we do know is that MPs can absorb a variety (hundreds) of different chemicals during their manufacture as and from the environment.

These chemicals include but are not limited to phthalates, organochlorine contaminants, organophosphorus esters, dioxins, antibiotics, tributyltin, bisphenol A, aluminium oxide, chromium, lead, cadmium and others.1 Many of these compounds are toxic or can disrupt the hormonal balance of the body (known as endocrine disrupting chemicals – EDCs). We have discussed how research has highlighted the problems with EDCs in mammals in another article.

MPs act as vectors for pollutants and toxins such as EDCs, heavy metals, pesticides and even pathogens.1 Once MPs enter the mammalian body, biomagnification and bioaccumulation processes make things worse (Trojan horse effects).

Research in aquatic mammals suggests that MPs can reduce energy reserves and feeding capacity.1 MPs can affect the reproductive system and damage the gut.1 MPs have also been linked to a depressed immune system, susceptibility to disease and, increased inflammation.1 The chemical pollutants associated with MPs have also been linked to cancer.1

Implications for Human Health

The implications of MPs for human health are many, and we will only touch on some of them here. Take cancer, for example. Most cancers (90-95%) are thought to result from a complex interaction of lifestyle factors – accumulated damage over a lifetime. The question naturally arises, how might MPs be affecting the risk of cancer in mammals? Currently, 168 pesticides are classified as potential carcinogens.4 MPs may act as vectors for these pesticides, carrying them into the body. Although the evidence is limited, this is not good news for our aquatic cousins or for us.

It should be noted, however that some researchers believe that the impact of MPs on human health is still uncertain and requires further research. This is undoubtedly true. However, the preliminary research that has been done in this area suggests that MPs could have a significant negative impact on our health.

You can read more about the implications of MPs for human health in this article.

The Solution?

The good news is that many consumers are already waking up to the plastic problem, even if they don’t necessarily know what to do about it. There are initiatives such as The Ocean Cleanup, which is doing an excellent job of removing plastic from rivers and oceans.

We need to change the way we interact with plastic. It is now impossible to imagine buying food without plastic. Everything is wrapped or contained in plastic! (Don’t be fooled by drinks in cartons, they are lined with a layer of BPA, even canned drinks are lined with plastic). I think the key to do this is to look at our recent past.

Almost all consumer food is wrapped in plastic in one way or another. But it doesn’t have to be this way. Milk used to be delivered in glass bottles, and then collected and reused. In Spain, wine used to be bought from a winery, you brought your bottle, and they filled it straight from the barrel. Meat was wrapped in kraft paper, and you put it in your bag, which you had to bring from home because plastic bags weren’t sold in those days.

I am not saying that we should go back in time. 100 years ago, life in Western nations was a lot worse for a lot of people*. We shouldn’t demonise fossil fuels because they have given us energy and allowed us to lift a lot of people out of poverty. But the plastic problem IS a problem, and my suggestion to it is to look at practices from the past.

Reduce, reuse, and recycle was common sense when we had less. We should offer consumers new ways to buy products without plastic. I would opt in for a milk bottle scheme, even if I had to take the empty glass bottle to the supermarket myself to refill it. The same applies to other consumables. Some consumers might not prefer this way of shopping, but at least it should be an option. We should be able to choose plastic-free goods if we want to. In this way, our food would have less contact with plastics and we would have less plastic to throw away.

*See “The Road to Wigan Pier” by George Orwell.

Conclusion

There is evidence to suggest that MPs may be having a detrimental effect on the health of aquatic mammal. This should concern us not only for the well-being of aquatic mammals, but for all life on earth, including ourselves.

While initiatives are underway to remove plastic from the oceans and rivers, we should change the way we interact with plastic. To do this, I suggest we remove plastic from the consumer chain as much as possible, or at least give consumers the option to go plastic-free.

If you liked this article, let us know in the comments. We love hearing your feedback. You can also email us directly at info@ecologica.life.

References

- The adverse health effects of increasing microplastic pollution on aquatic mammals.

- Release of Microplastics from Discarded Surgical Masks and Their Adverse Impacts on the Marine Copepod Tigriopus japonicus.

- Investigating microplastic trophic transfer in marine top predators.

- A tiered approach to prioritizing registered pesticides for potential cancer hazard evaluations: implications for decision making.